Aejang Project

(on-going)

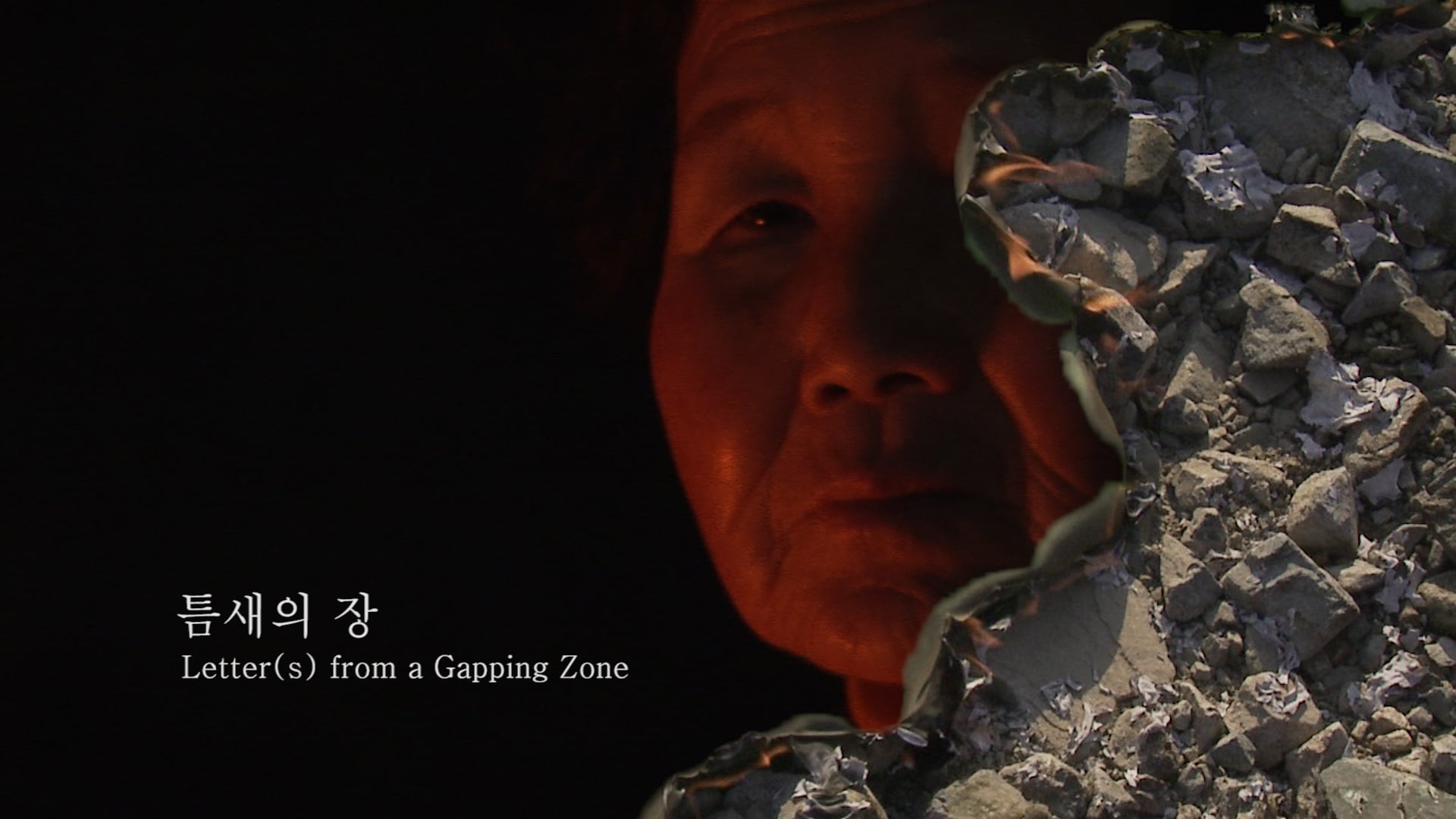

The conception of this project has initially begun when Park first heard about his father’s oldest memory: The moment when he went up a mountain with my grandfather to bury his one-year-old sister's corpse - he was about three years old. Park’s aunt was not the only infant death in the village, and they were, including his father's sister, buried in the form of aejang.

In Korea, aejang indicates both the traditional ritual of burying children who have passed away in their infancy and the grave itself. Infants who passed away due to poverty and diseases were, in the past, seen as bad luck. Thus, the tradition itself is designed to forget: the child is buried in the dark, at night, without the mother present, under a pile of rocks that will slowly dissolve away, becoming part of the natural surroundings. The body is usually wrapped in hemp; the smell of cannabis will help the “death messengers” find the lost soul and guide the child to a better next-life. These children were typically excluded from family trees. The phrase “burying something in one’s heart” possibly traces its origins to this practice. With Korea’s economic development, aejang has faded, much as those who experienced it chose to forget and focus on surviving the turmoil of their times.

Taking this part of his family history, Park contemplates the ontological relationship between heritage and a diasporic being, framing history as “a disappearance that does not disappear,” and ponders the possibility of consolation with his generational trauma, caused by both personal and historical narratives, by taking an active part in the processes of forgetting/letting-go – suggesting the act of grieving and acceptance as an act of embodied recollection and reconnection of the physical and temporal distance laid between heritage/history and a diasporic body.

2025

2023

Starting Point